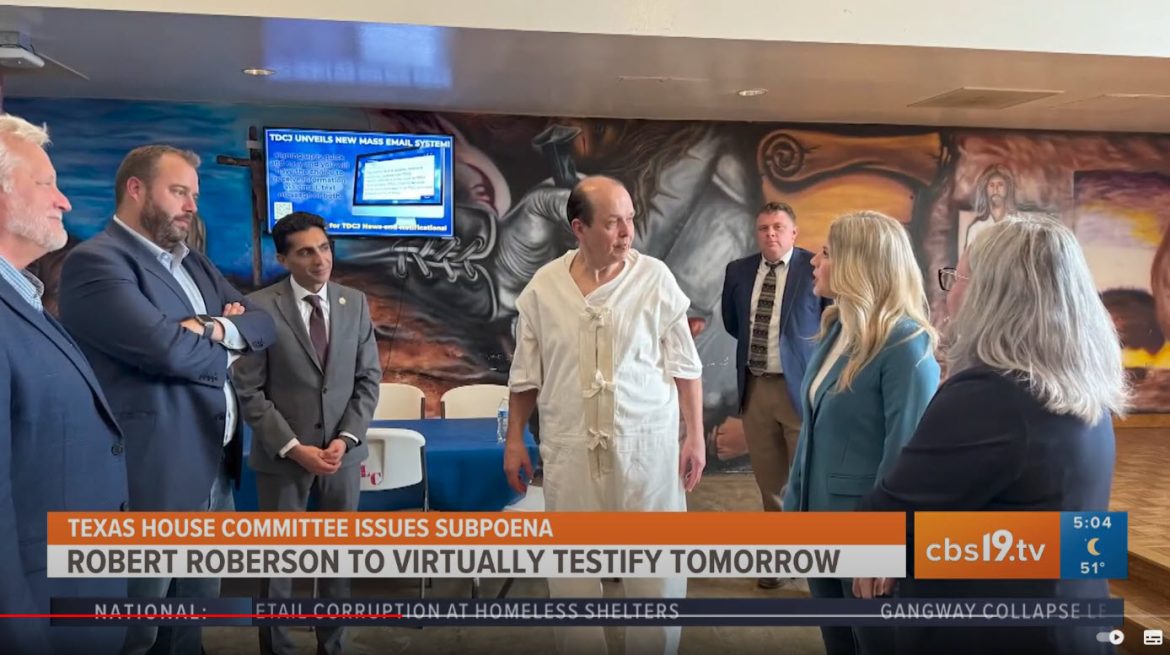

In an unprecedented development, Robert Roberson, a Texas man convicted of killing his two-year-old daughter in 2002, is set to testify today before a Texas House committee after narrowly avoiding execution last week. Roberson, whose case has been embroiled in controversy due to the now-debunked theory of “shaken baby syndrome,” was scheduled to be executed, but a last-minute subpoena from a bipartisan coalition of Texas lawmakers has delayed his death sentence. This marks the first time the Texas Supreme Court has intervened to halt an execution under such circumstances.

Roberson’s testimony will focus on his claim that his daughter died of natural causes rather than as a result of abuse. His defense argues that the child was suffering from pneumonia and taking a medication that has since been discontinued due to its potential to cause fatal breathing complications. The case has ignited widespread debate over the use of outdated scientific evidence in the courtroom, with much of today’s hearing set to examine the state’s “junk science law,” which aims to overturn convictions based on discredited science.

Legal experts point to “shaken baby syndrome” as a flawed diagnosis that has led to numerous wrongful convictions across the country. To date, there have been 32 exonerations of individuals initially convicted under this theory. Roberson’s case has now become the latest flashpoint in this ongoing debate, as both Democrats and far-right Republicans united in a rare moment of cooperation to stop his execution. Scott Braddock from The Quorum Report describes the bipartisan effort as “uncharted waters” for the Texas legislature.

The push to halt Roberson’s execution gained momentum after former police officer Brian Wharton, who had been instrumental in securing Roberson’s conviction, publicly called for clemency. Wharton, now convinced of Roberson’s innocence, revealed that the case “eats at him every day” and is urging Texas Governor Greg Abbott to grant a one-time, 30-day reprieve to allow courts more time to review the evidence. Despite this plea, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles has already denied Roberson’s clemency request.

In addition to Wharton’s advocacy, Roberson’s attorney, Vanessa Potkin, has emphasized the importance of reexamining the medical evidence, especially given that the medication the child was taking has since been pulled from the market for causing severe respiratory problems in young children. Potkin remains confident that her client will ultimately receive a reprieve.

Last week’s dramatic back-and-forth between Roberson’s defense team, state lawmakers, and the courts culminated in an emergency hearing before the Texas Supreme Court, which resulted in the unprecedented decision to stay his execution. As Roberson appears before the committee today, many legal and political observers see this as a critical test of Texas’ approach to the death penalty in cases involving questionable scientific evidence.

As the hearing unfolds, it remains unclear what impact Roberson’s testimony will have on his ultimate fate. However, the case has already sparked a renewed conversation about the reliability of forensic science in capital punishment cases and the broader implications of executing individuals based on outdated or discredited evidence.